Our thoughts on personhood credentials and digital identity

Turn your texts, PPTs, PDFs or URLs to video - in minutes.

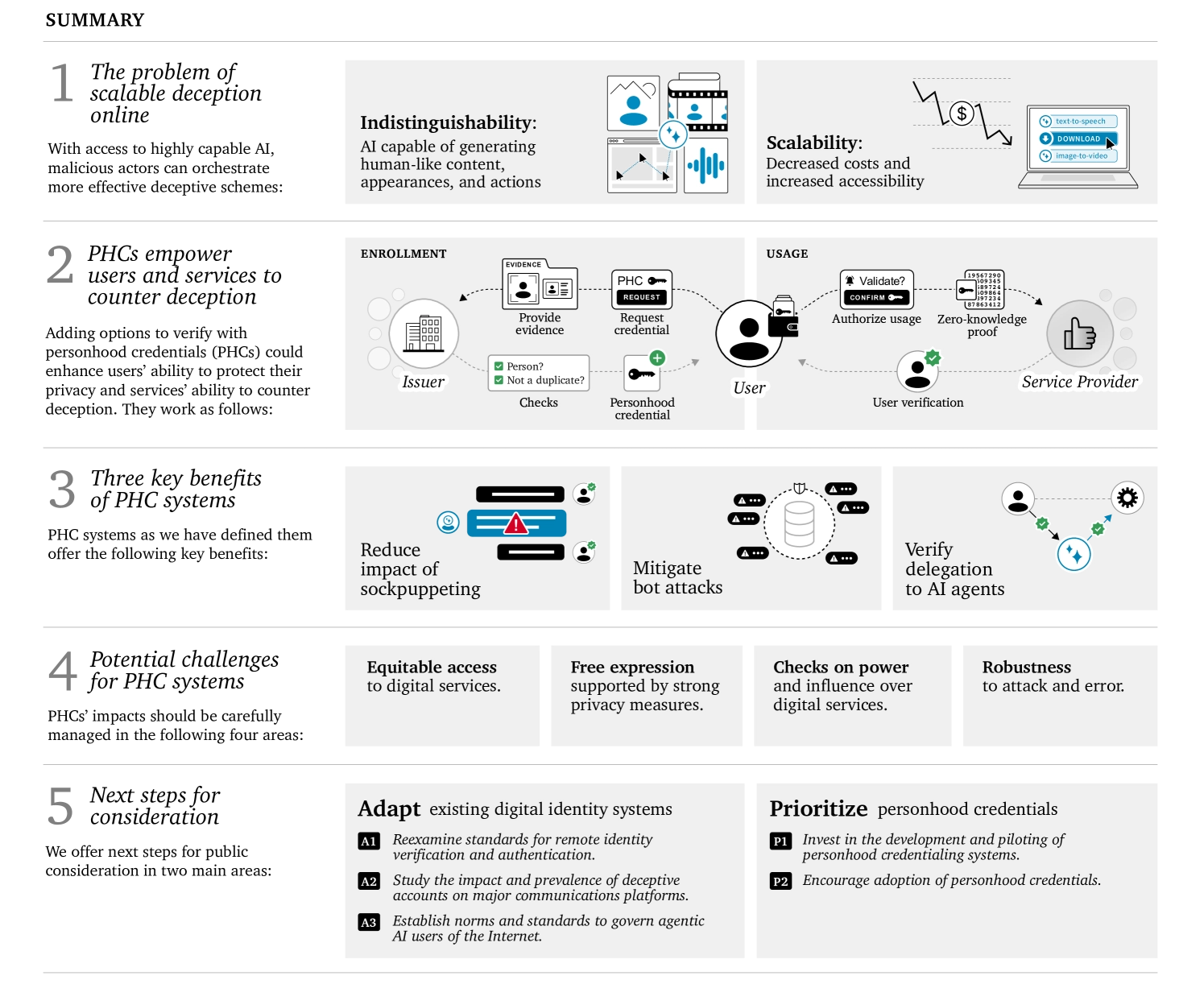

Today, the MIT Technology Review published an article reviewing a pre-print paper from OpenAI, Harvard University, Microsoft, University of Oxford, MIT and others which proposes a new tool called personhood credentials (PHCs) that allows internet users to demonstrate that they are real people (rather than AI agents) to online services, without disclosing their personal information.

The MIT Technology Review article includes a few quotes from Synthesia about PHCs but I thought I'd share our thoughts in full, for those of you who are interested to know how we approach the concept of digital identity on our platform.

To start with, there are no current foolproof ways for someone to prove they’re a human online. We feel the PHC system could represent an improvement on those current methods, but it needs to be very carefully considered from various regulatory and implementation perspectives. For example, how do we correctly incentivize service providers to implement PHCs in a desirable, robust, secure fashion without creating inappropriate amounts of friction for users?

We may end up in a world in which we centralize even more power and concentrate decision-making over our digital lives, giving large internet platforms even more ownership over who can exist online and for what purpose. And, given the lackluster performance of some governments in adopting digital services and autocratic tendencies that are on the rise, is it practical or realistic to expect this type of technology to be adopted en masse and in a responsible way by the end of this decade?

The paper also identifies two important trends in AI development that may contribute to more effective deception online:

- Users powered by AI systems are increasingly indistinguishable from people online. For example, AI-powered accounts can be populated with realistic human-like avatars that share high-quality content and that take increasingly autonomous actions.

- Second, AI is becoming increasingly more affordable and accessible, which can help for achieving many benefits but can also enable a larger amount of deception online.

We agree that establishing whether someone is real on the internet is a problem that will grow rapidly in the foreseeable future, and there are risks associated with the irresponsible use of generative AI systems. To mitigate these risks, we've taken several measures to keep our platform safe from abuse.

First, we believe people should have the right to own their image and be able to decide how it's used. This means we do not create an AI avatar without someone’s consent. Therefore, proving whether someone is an actual human is a critical part of our consent gathering workflow, though this goes beyond the scope of the concept of PHCs. That's because we need to know not only that a user is a person, but also that they are indeed the right person; in other words, we want to avoid creating non-consensual deepfakes, where someone clones another person without their permission.

The distinction is important because we’ve already seen what happens when you unleash this technology without the right guardrails in place.

When we create an AI avatar of someone, we use a consent gathering process that takes place either in person for avatars created in a studio or online for Personal Avatars created remotely from a laptop or phone. We also use account-level information to establish whether businesses are real entities and we provide a limited feature set for non-paying users. In this context, PHCs could be useful in ensuring a responsible use of the platform, in line with our terms of service but this requires careful consideration, as the paper suggests.

Secondly, if we think about the state of AI generated media three to five years ago, it was mostly an academic conversation as the quality of most AI tools was nowhere near what humans could create. But it’s clear that three to five years from today, AI platforms will match or surpass the skills of an average content creator, meaning people will be able to make Hollywood-quality videos from a laptop. At the moment, we’re in this halfway place where some content generated with AI is great but some is not, which makes it difficult and confusing to distinguish between what’s created with traditional cameras and software and what is entirely digitized with AI.

To prove whether we can safeguard our platform from bad faith actors, we recently conducted a threat intelligence report and performed a red team exercise designed to stress test our ability to detect inauthentic behavior and harmful content. The red team test had many interesting findings, but perhaps the most interesting insight is related to product decisions we've made and how they act as a financial deterrent against misuse. Most bad faith actors are looking for platforms that are easy to use and cheap to abuse, especially those that lend themselves to being exploited by AI bots. We've also chosen to impose strict rules for offenders; for example, if your video breaks our rules or your account is disabled, you can appeal our decision but you do not get a refund. Combined with our robust content moderation and strict refusal to generate non-consensual deepfakes, this becomes a real problem for AI-powered bad faith actors, because using our platform becomes financially burdensome. Our approach is in contrast with our competitors' who either employ no content moderation or refund offenders when they break the rules, therefore creating a strong incentive for them to keep abusing those platforms.

The PHC paper also does a good job of pointing out the risks and limitations of this system. For example, it could lead to systemic misuse through backdoors, allowing even more effective sockpuppeting or misinformation campaigns to be conducted by state actors, given the increased trust through perceived PHC validation. In addition, the system would rely heavily on the correct implementation practices of the service on the provider side without requiring strong transparency around said implementation, which could lead to misleading or ineffective implementations, whether intended or not.

While time will tell whether PHCs as suggested are the right solution or will be practical to implement, we appreciate these efforts and believe that they are a necessary and important step in the right direction.

About the author

Martin Tschammer

Martin Tschammer

Martin Tschammer is the Head of Security at Synthesia.